"Abstraction excentrique"

Jean Dewasne,

Mathieu Matégot,

Nicolas Ionesco,

Nino Calos,

Yves Laloy,

Yves Millecamps

With Nino Calos (1926, Messina – 1990, Paris), Jean Dewasne (1921, Lille – 1999, Paris), Nicolas Ionesco (1919, Bucarest – 2008, Malakoff), Yves Laloy (1920, Rennes – 1999, Cancale), Mathieu Matégot (1920, Hongrie – 2001, Angers), Yves Millecamps (1930, Armentières, lives in Poissy)

Acknowledgements: galerie Chevalier, Paris; Perrotin, Paris; RCM Galerie, Paris.

In 1966, at the Fischback Gallery in New York, Lucy Lippard invited eight artists—Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Gary Kuehn, Bruce Nauman, Don Potts, Keith Sonnier, Frank Lincoln Viner, united under the banner of a hypothetical Eccentric Abstraction.

These eccentrics— hastily but insightfully brought together by the young New York critic—were not on the radar of American abstraction, still under the sway of abstract expressionism. The lineup included figures whose eccentricity would remain entirely true to Lippard’s statement: “An attempt to blur boundaries…between minimalism and something more sensuous and sensual…”1

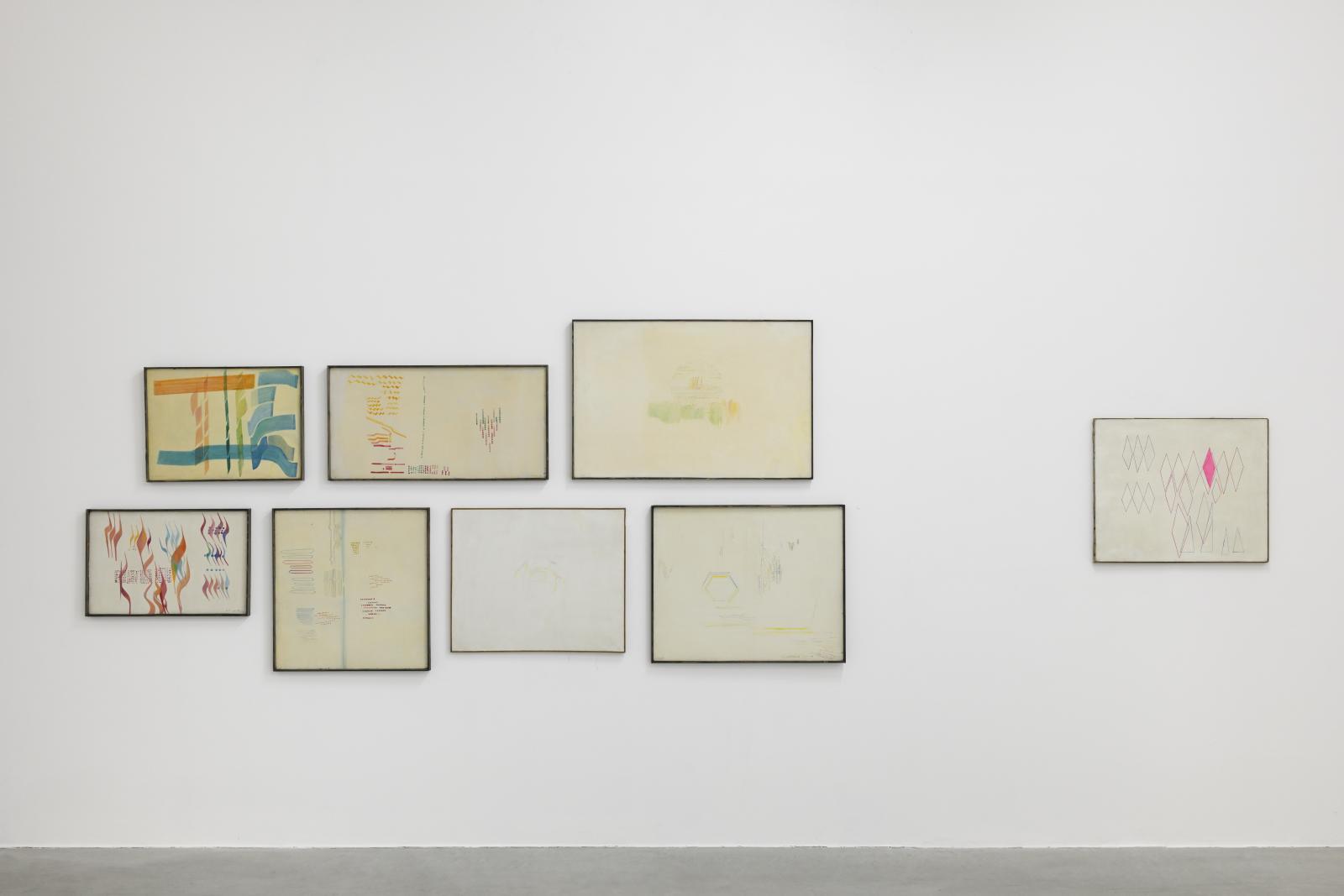

A tribute to Lucy Lippard, now retired in a remote area of New Mexico, curators Seungduk Kim and Franck Gautherot have given a French slant to what is still a magnificent exhibition title, 'Abstraction Excentrique', by gathering artists who were active in Paris between the 1950s and 1970s.

Delving into the twists and turns of geometric abstraction, whose tangents, since César Doméla, have softened the rigid right angles, six long-overlooked or forgotten artists are now assembled on the walls of the Consortium Museum, in a confrontation of painting and tapestry on the margins of the familiar revivals the art world regularly stages.

Some of them forged their careers within the official circles of the Académie de Beaux Arts: Jean Dewasne, for instance, succeeded Hans Hartung, before eventually passing the baton to Yves Millecamps.

Immersed in stylized modernist aesthetics, once dismissed as outdated and now back in fashion, this cohort of artists—united here under the umbrella of eccentricity—enters the pantheon of rediscoveries, reappraisals, and shifting tastes, for which the Dijon institution has developed a special savvy.

From the start of the exhibition a hypothesis emerges in which tapestry, inherently decorative, immediately reveals its kinship with painting. The art of weaving and the art of painting are in harmony, making a joint statement about the art hanging on the walls.

Throughout the classical era, tapestry had sought to rival painting in an endless contest of virtuosity by multiplying its colors and refining its threads to match the infinite palette of colors available to painters. In vain. With a bold iconoclastic spirit, a new generation of artists— Lurçat, Picart Ledoux, Dom Robert, and others— set out to dismantle such sophistication, replacing it with flat areas of color, strong outlines, primary hues, and distinct tones, introducing original formal and stylistic novelty. The enthusiasm was so great that this artistic category earned its own biennial in Lausanne, which showcased over six hundred artists from around the world from 1962 to 1995.

Mathieu Matégot, the famous designer known for his perforated sheet metal and raw industrial furniture, also indulged in the pleasures of woven yarn with blurry, tangled patterns set against black backgrounds.

Five pieces woven between 1955 and 1975 attest to a style in which the nervous, hatched lines delineate areas outlined in white and submersed in the deep black of the background (Fiction, c. 1955, Omar Khayyam, c. 1955, Le Parkhor, c. 1955). This approach later developed into a more classical fullness, with colorful abstraction in compositions that fill the entire woven surface (Tropique du Cancer, c. 1975, Terra Nostra, c. 1975).

The pictorial counterpoint is provided by Yves Laloy, the post-Kandinsky figure from Rennes—a hybrid artist and recognized surrealist, championed by Breton himself on the cover of Surrealism and Painting, republished by Gallimard in 1965, with his famous painting Les petits pois sont verts, les petits poissons rouges, (Peas Are Green, Little Fish Are Red,1959). He was also a painter of geometric abstraction, working in an almost orthonormal lineage (having drawn architectural plans on a drafting table in his former profession as an architect). An abstract painter of diagonals, too, whose colorful dynamism spreads across briskly painted backgrounds scattered with dots-lines-planes, and triangle arrows, creating a pictographic painting style that invites exploration and delight.

The second section opens the doors to the glorious, dominant, official, and academic story of an artist from the North, Jean Dewasne, born in Quiévy like his predecessor Auguste Herbin. Bringing “logotyped” geometric abstraction to its pinnacle, his work resonated with the visual taste of his time (the design-driven 1960s), only to be later forgotten.

The convergence of a visual aesthetic in the major arts with fashion, industrial design, graphic arts and advertising, boosted Dewasne’s national and international reputation, until the soft, muted, zen tones of burnt siena and faded greens of the following decades left him out of the spotlight.

Enameled in industrial colors, the paintings are glossy, precisely composed with tape, featuring an imbricated figure/ground dialectic of curved shapes outlined with fine white lines at times. The palette is often limited to pure white, red, black, blue, and green applied in solid flat areas. Large-scale mural commissions flourished, commanding a strong, and perhaps overpowering, environmental presence, yet managing to remain strictly within pictorial two-dimensionality. Not any 3D kinetic effects here! The temptation toward sculpture nonetheless arose in his Antisculptures, which used motorcycle tank parts as supports, or elements from car bodies, in collaboration with Régie Renault.

The exhibition continues with another artist from the North, Yves Millecamps, born in 1930 in Armentières.

Following in the footsteps of Jean Lurçat, Millecamps began his career as a tapestry cartoon painter after studying at the École des Arts Décoratifs. He quickly moved away from Lurçat’s vegetal and symbolic lyricism, inventing a form of “untangled” deconstructed abstraction, in which drawn lines are detached from the central motifs.

From 1963 onward, he added oil paint and later acrylic to his tapestries. His abstraction became structured, geometric and orthogonal, rigorously controlled using rectilinear tape. The color palette is broad, and the chromatic relationships are highly sophisticated. His compositions gradually filled up the entire surface of the canvas and are unique, owing nothing to any of the abstract painting trends.

In retrospect, we can detect a visual language that flourished later in the 1990s on posters, flyers, and album covers for techno music, concomitant with the rise of digital tools and the new computers so popular among graphic artists of the time.

In the depths of the artist’s studio, we saw dozens of labeled color tests, which along with preparatory stencils logically led to the large-scale paintings.

The last gallery offers a display of work by two even more singular artists.

Nino Calos (born Antonio Calogero, 1926, Italy—1990, Paris) is a pioneer of lumino-kinetic art. He settled in Paris in 1956, where he joined the capital’s prominent avant-garde. His first light boxes (1956-1957), with their slowly shifting atmospheric colors, secured him a unique place within this artistic orbit, a spin-off from geometric abstraction, whereby he was dubbed an abstract impressionist!

Close to Frank Malina and Nicolas Schöffer, who also experimented with lumino-kineticism, Calos’s works stood out for their pictoriality, as Frank Popper stated: “His luminous Mobiles express a highly personal style: a calm poetic movement in unison with a colorful chant.” Other commentators underscored the cosmic and lyrical character of his abstraction and pointed out how he had succeeded in “using electricity to provide both light and movement and adopting cold scientific materials, while remaining a painter and a poet.”

His work was included in many group shows at galleries and was also featured in the acclaimed exhibition 'Light and Movement', held at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1967 and co-curated by Frank Popper.

The luminous pictorial quality of his boxes does not overshadow his practice as a painter on canvas, whose paintings may appear to be still images of his moving compositions.

Nicolas Ionesco (1919, Bucharest—2008, Malakoff) arrived in Paris in 1945, where he began his artistic training in Fernand Léger’s studio. His early abstract works show a clear influence from his professor, but he soon moved in another direction, favoring red and black geometric compositions with flat uniform areas of color. His highly orthogonal compositions gradually softened, shifting to more biomorphic vibrating forms with light colors applied on pristine white backgrounds. The pictorial events became increasingly simplified, eventually leading to “color alone,” the vibrant bright yellow monochromes that earned him international recognition.

Believing he had exhausted and brought his research to a final conclusion, he withdrew entirely from the art world to spend a period in deep spiritual reflection. He resumed painting, drawing inspiration from early Christian frescoes in Romanian Orthodox monasteries. New styles and subjects followed almost yearly in paintings with flat areas of color and stylized figures floating against solid monochrome backgrounds. Coming full circle, the last paintings hark back to the constructed abstraction and primary colors of his early work.

— Frank Gautherot and Seungduk Kim

—

1. Lucy R. Lippard, “Landmark Exhibitions Issue: Curating by Numbers,” Tate Papers, no. 12 (2009).